The Captivating History of Dream Interpretation?—?Gilgamesh to Freud

If you’ve ever wondered what your crazy dreams might mean, you’re not alone. People have been attaching meanings to their dreams for millennia?—?as long as civilisation itself existed. Today we explore some of the history behind this dreaming phenomenon.

Mesopotamia (2100 BC)

One of the earliest written examples of dream interpretation comes from the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh dreamt that an axe fell from the sky. The people gathered around it in admiration and worship. Gilgamesh threw the axe in front of his mother and then he embraced it like a wife.

After he woke up, his mother Ninsun interpreted the dream. She said that a powerful man would soon appear. Gilgamesh would struggle and try to overpower him, but he wouldn’t succeed. Eventually they would become close friends and accomplish great things.

She added, “That you embraced him like a wife means he will never forsake you. Thus your dream is solved.”

This example shows our tendency to see dreams as predictions of future.

Ancient Greece

Artemidorus of Daldis, who lived in the 2nd century AD, wrote a comprehensive text Oneirocritica (The Interpretation of Dreams).

Although Artemidorus also believed that dreams can predict the future, he used many contemporary approaches to dreams.

For example, he thought that the meaning of a dream image could involve puns and could be understood by decoding the image into its component words.

In one story, Alexander the Great, while waging war against the Tyrians, dreamt that a satyr was dancing on his shield. Artemidorus reports that this dream was interpreted as follows: satyr = sa tyros (“Tyre will be thine”), predicting that Alexander would be triumphant.

Additionally, ancient Greeks had multiple gods of dreaming which were collectively called the Oneiroi (???????, literally “Dreams”).

Some worth mentioning are Morpheus, Phantasos, and Phobetor.

According to Hesiod (a Greek poet), they were the sons of Nyx (goddess of night) and the brothers of Hypnos (god of sleep), Thanatos (god of death), Geras (god of old age).

Christianity

Dreams were always an integral part of the Christian faith. In fact, the Bible even mentions that Joseph was known as a dream interpreter.

There are several dream-interpretation stories recited in the Bible (examples include Pharaoh’s dream in Genesis 41 and Paul’s visions in Acts).

And there are also a couple scriptures that discuss dreams in general, or visions as they were commonly referred.

One of them is Joel 2:28 which states:

“And afterward,

I will pour out my Spirit on all people.

Your sons and daughters shall prophesy,

your old men will dream dreams,

your young men shall see visions”.

There’s even a skeptical side to scripture in regards to dream interpretation, for example in Zechariah 10:2 “the dreamers tell false dreams, and give empty consolation”.

These scriptures provide insight into the idea that dreams have been an integral part of divine communication in Christianity ever since its infancy.

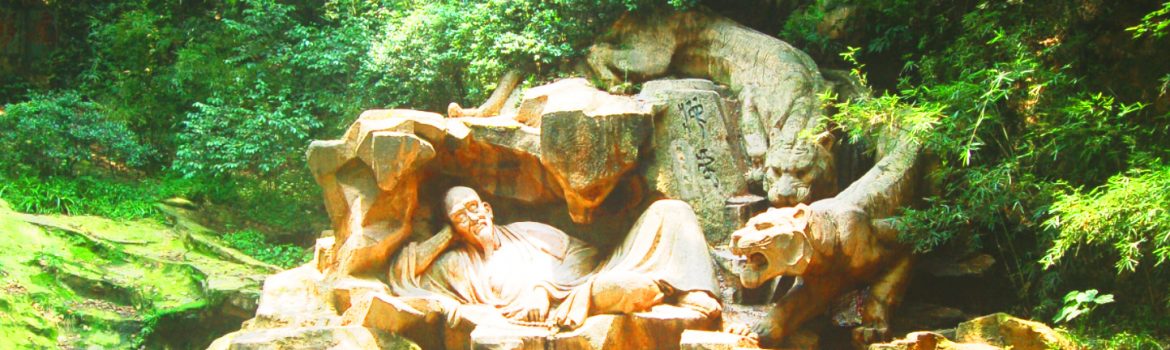

China

The traditional Chinese book on dream-interpretation is the Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation (????), compiled in the 16th century by Chen Shiyuan.

Chinese thinkers had raised profound ideas about dream interpretation, such as the question of how we know we are dreaming and how we know we are awake.

For example, Chuang Tzu in his self-titled book wrote:

“Once Chuang Chou dreamed that he was a butterfly. He fluttered about happily, quite pleased with the state that he was in, and knew nothing about Chuang Chou.

Presently he awoke and found that he was very much Chuang Chou again. Now, did Chou dream that he was a butterfly or was the butterfly now dreaming that he was Chou?”

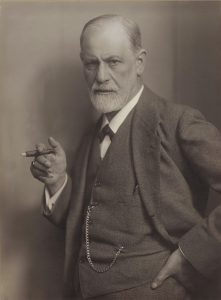

Sigmund Freud

It was in his book The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung), first published in 1899, that Sigmund Freud first argued that the motivation of all dream content is wish-fulfilment; and that the reason for a dream is often to be found in the events of the day preceding the dream, which he called the “day residue.”

Freud further considered that the experience of anxiety dreams and nightmares was the result of failures in the dream-work (distortions that he claimed were applied to repressed wishes while recollecting the dream).

Rather than contradicting the “wish-fulfilment” theory, such phenomena demonstrated how the ego reacted to the awareness of repressed wishes that were too powerful and insufficiently disguised.

He later admitted traumatic dreams (where the dream merely repeats the traumatic experience) as exceptions to the theory.

Carl Jung

Although he didn’t dismiss Freud’s model of dream interpretation, Carl Jung believed Freud’s notion of dreams as representations of unfulfilled wishes to be limited.

Jung argued that Freud’s procedure of collecting associations to a dream would bring insights into the dreamer’s mental complex?—?a person’s associations to anything will reveal the mental complexes, as Jung had shown experimentally?—?but not necessarily closer to the meaning of the dream.

Jung proposed two basic approaches to analysing dream material: the objective and the subjective.

In the objective approach, every person in the dream refers to the person they are in real life: mother is mother, girlfriend is girlfriend, etc.

In the subjective approach, every person in the dream represents an aspect of the dreamer. Jung argued that the subjective approach is much more difficult for the dreamer to accept.

Dream interpretation today

In one study conducted in the United States, South Korea and India, it was found that 74% of Indians, 65% of South Koreans and 56% of Americans believed their dream content provided them with meaningful insight into their unconscious beliefs and desires.

Not all dream content was considered equally important, however.

Participants in the studies were more likely to perceive dreams to be meaningful when the content of dreams was in accordance with their beliefs and desires while awake.

In another words, they believed a positive dream about a friend to be meaningful more often than a positive dream about someone they disliked, and vice versa: they were more likely to view a negative dream about a person they disliked as meaningful than a negative dream about a person they liked.

Epilogue

It’s very clear that dreams have boggled our minds forever. Why do we get them? What do they mean? Can we take control of them?

Well, some people regularly do take control of their dreams, which allows them to do anything they want, whenever they want. That phenomenon is called lucid dreaming.

ViviDream has developed a supplement to help induce this state of lucid dreaming. If you’d like to experience your childhood again, or embark on an unforgettable adventure, or perhaps have sex in a dream, you might want to give LucidEsc a try. Just click the image below!

[TheChamp-FB-Comments]

Further reading:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dream_interpretation

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oneiroi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhuang_Zhou

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhuangzi_(book)

References:

-

Morewedge, Carey K.; Norton, Michael I. “When dreaming is believing: The (motivated) interpretation of dreams”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 96 (2): 249–264. doi:10.1037/a0013264. PMID 19159131.

-

^ Thompson, R. (1930) The Epic of Gilgamesh. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

^ George, A. trans. (2003) The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

-

^ Oppenheim, A. (1956) The interpretation of dreams in the ancient Near East with a translation of an Assyrian dreambook. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 46(3): 179–373. p. 247.

-

^ Artemidorus (1990) The Interpretation of Dreams: Oneirocritica. White, R., trans., Torrance, CA: Original Books, 2nd Edition.

-

^ a b Freud, S. (1900) The Interpretation of Dreams. New York: Avon, 1980.

-

^ (Haque 2004, p. 376)

-

^ (Haque 2004, p. 375)

-

^ (Haque 2004, p. 361)

-

^ (Haque 2004, p. 363)

-

^ Lutz, Peter L. (2002), The Rise of Experimental Biology: An Illustrated History, Humana Press, p. 60, ISBN 0-89603-835-1

-

^ Ibn Khaldun, Franz Rosenthal, N.J. Dawood (1967), The Muqaddimah, trans., p. 338, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01754-9

-

^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, “Inner Chapters 1–4”

-

^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, “Inner Chapter 5”

-

^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, “Inner Chapters 6–9”

-

^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, “Inner Chapter 10”

-

^ Johnson, M.; Kahan, T.; Raye, C. (1984). “Dreams and reality monitoring”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 113: 329–344. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.329.

-

^ Blechner, M (2005). “Elusive illusions: Reality judgment and reality assignment in dreams and waking life”. Neuro-Psychoanalysis. 7: 95–101. doi:10.1080/15294145.2005.10773477.

-

^ Matalon, Nadav (2011). “The Riddle Of Dreams”. Philosophical Psychology. 24 (4): 517–536. doi:10.1080/09515089.2011.556605.

-

^ Wilson, Cynthia (3 April 2012). “Remembering and Understanding your Dreams”. Womenio. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

-

^ Gray, R. (9 January 2012). “Lecture Notes: Freud’s Conception of the Psyche (Unconscious) and His Theory of Dreams”. University of Washington. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

-

^ Freud, S. (1900) op.cit., (1919 edition), p. 397

-

^ Jung, C.G. (1902) The associations of normal subjects. In: Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–99.

-

^ Jacobi, J. (1973) The Psychology of C. G. Jung. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

-

^ a b Storr, Anthony (1983). The Essential Jung. New York. ISBN 0-691-02455-3.

-

^ Jung, C.G. (1948) General aspects of dream psychology. In: Dreams. trans., R. Hull. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974, pp. 23–66.

-

^ Jung, C.G. (1948) op.cit.